Community |

|

| From 1910 to 1955, Ferguson WAS the railroad. The railroad WAS Ferguson. The railroad laid out the town and named it after district executive Edward Ferguson, who supervised the laying of the rails. The railroad built the school, financed it for 45 years, and took care to make sure it was well run, since it served employees' children and trained future railroad workers. Until the railroad closed its shops, it loaded the senior class on its own passenger cars every year and took them to Florida on their annual Senior Trip. The train shown here at right is the last one Ferguson seniors rode South. (After the railroad left, Ferguson continued the senior trip using its own bus.) The railroad not only paid excellent wages, but provided employees' families comprehensive health and dental care, gave each family a turkey at Thanksgiving and Christmas and a ham at Easter, gave two weeks a year paid vacations, supplied free coach fare on its passenger trains, and granted a generous pension upon retirement. |  |

|

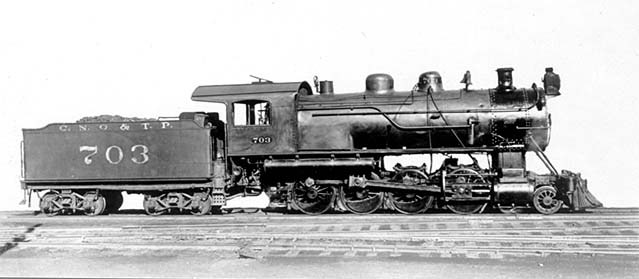

Ferguson's foundation was the Southern Railroad in the age of steam engines. This 2-6-2 engine was one of the Southern's greatest ever, but it had a limited range. It needed complete servicing in a fully equipped rail yard. The Southern built one of those yards in South Somerset and renamed it Ferguson after the chief executive. The Ferguson Yard employed 600 men at high salaries and full benefits, working them seven days a week. Since few people then owned vehicles, men and families needed to live within walking distance. The railroad built four additional blocks of small frame houses in South Somerset and renamed the community Ferguson. The school at Somerset did not offer bus service so the railroad built its own along the tracks at the south edge of town. During the 1920s, 30s and 40s, in some years the railroad hired every boy graduating or dropping out except for those entering the armed forces. A Ferguson boy with the grades could have his way paid to college if he majored in engineering and signed a binding contract to work for the railroad. |

| Boys without the math skills but manual dexterity could attend the railroad's own school in Knoxville and earn certification as a machinist, returning to Ferguson for a very good paying career. Even high school dropouts could begin as "gandy dancers," workers with strong backs and good hands who rode small "gang cars" up and down the tracks checking for flaws or rough spots and repairing them. A boy could begin that way and work his way up, perhaps by his mid 20s qualifying for machinist school or even the engineer program in Chattanooga. 27 Ferguson graduates eventually became locomotive engineers, the most glamorous job on the railroad. The railroad's retirement and health care programs were so good the US government used them for the model for Social Security and Medicare. During the 1930s and 40s the Ferguson Yard was at its peak. During World War II Southern trains were hauling troops and military supplies. During the decade after the war the nation was converting back to a consumer economy and railroads hauled the autos, appliances and other goods people had done without for 10 years. |  |

|

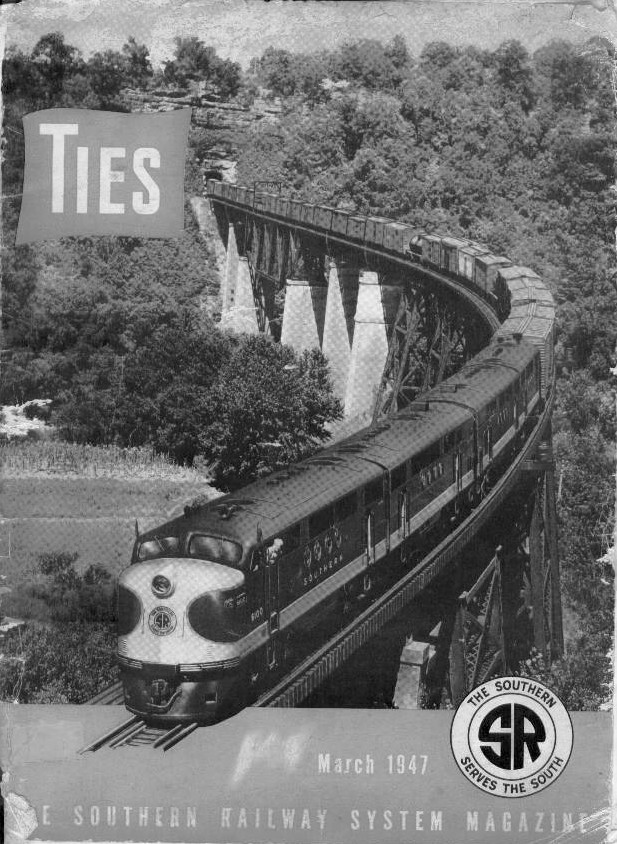

But in the 1950s two trends meant decline for Ferguson Yard. First, the automobile replaced the passenger train as the favorite means of transportation. This reduction in passenger trains meant less Chicago - Atlanta - Miami traffic, and fewer locomotives needing serviced. Even worse, diesel engines shown at left replaced big steam engines. Diesels could run from Cincinnati to Chattanooga without servicing, so Ferguson Yard was obsolete. 600 jobs fell to 400, then 200, then 100, 50 and finally the yard closed altogether. Ferguson's main reason for being was gone. Many of the men were offered jobs in Knoxville, Chattanooga, Cincinnati or Atlanta by the railroad, but in leaving they took their children with them. Ferguson enrollment began slipping. |

| L to R Front Muse and Yahnig, Rear Helton and Minton (no first names available) in April 1909 on the main line South of Elihu. These are adults, but later many Ferguson high school graduates or even dropouts often began their railroad careers as "gandy dancers." Four man crews operating out of the Ferguson Yard maintained the rails south to the Tennessee state line and north to Stanford. They would hand crank this little machine along the track, checking proper alignment, ballast, tie quality, and other details. When they found anything amiss, they would dismount and repair it. if they found problems with bridges, road crossings or tunnels they would return to the Yard and file a work order for a major crew to proceed to the area and make the repairs. A Ferguson gandy dancer worked seven 10 hour days a week, but started at $6000 a year when the average American male earned $4000 - $5000 a year. |  |

|

This was Ferguson Station, the old passenger depot. It was very rare for a railroad to maintain two full sized passenger stations only a mile apart, and the Somerset Station was just up the tracks. But Ferguson was the maintenance headquarters of the railroad and executives came and went daily. They did not intend to get on and off the trains at a less than impressive station, and they had no patience for commuting back and forth from the Somerset Station. This station had executive class amenities : classy restrooms, more comfortable benches, and very long covered walkways so passengers could walk to their passenger cars in the shade or protected from rain. Full sized cities (Cincinatti, Lexington, Knoxville, Chattanooga and Atlanta) obviously had larger and fancier stations, but of all the small town stations along the Southern routes, this was the best, a fact that often irritated Somerset riders. Danville (Ky.), and Dalton and Marietta (Ga.) had very similar stations without the nice restrooms or long covered walkways. This photo was provided by the Helton family. |

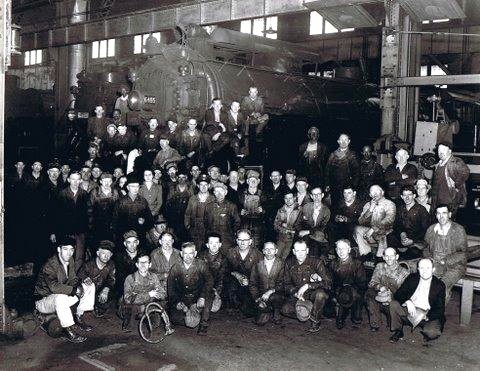

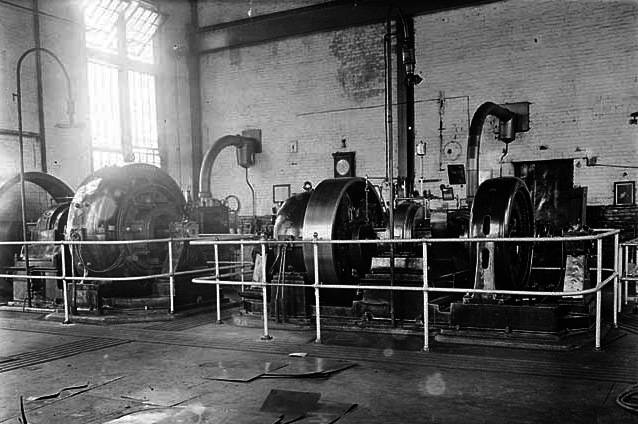

This great photo was provided by the Richardson family. It shows the full Ferguson Maintenance Yards with all buildings still in place on a dreary November afternoon. Maintenance has already been moved to Chattanooga so there is little activity but the heat is still on in all buildings, as indicated by the smoke coming from the stack, which extends up from a coal fired furnace. This is what the yards looked like from the top floor of Ferguson School. The track in the lower right is one of the mainline tracks running right behind the school. In those days the mainline consisted of two tracks, one for trains heading North and one for trains heading South. For a view inside the large complex to the left, which was the engine house, see top right. The full "shift" poses in front of a 2-6-2 steam engine having just been reconditioned. A shift was one eight hour work group. The yard operated 24 hours a day seven days a week, with midnight - 8 am, 8 - 4 pm and 4 pm - midnight shifts. |

|

|

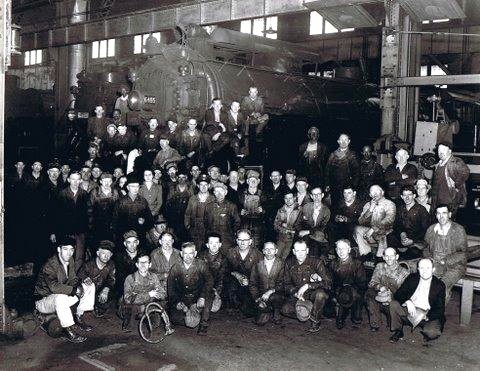

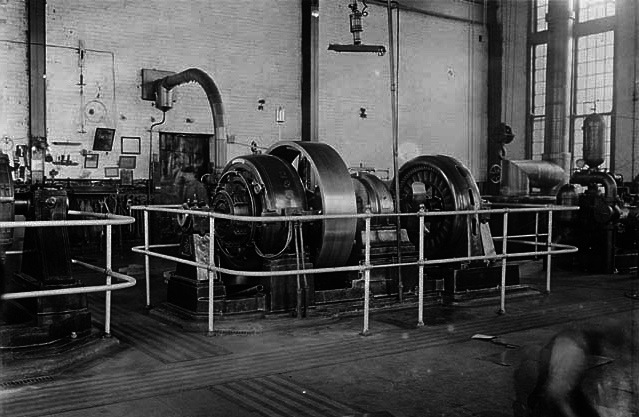

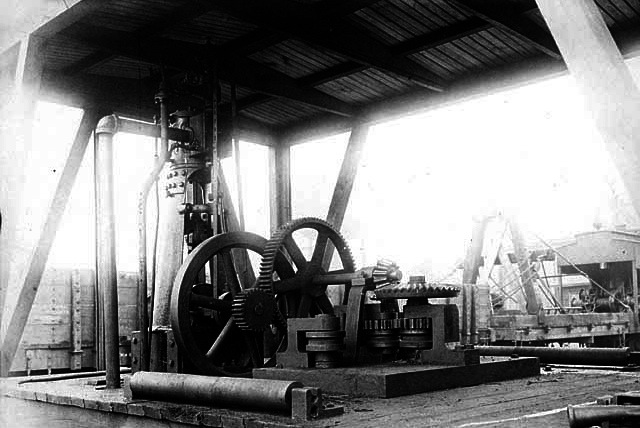

This is the interior of the smaller building in the center of the photo above. This was the machine shop, where highly specialized machinists could create any part used on any engine or car used on the Southern Railroad. They did not have to order parts from a central supplier. They made their own. And for half a century, they made them right here in Ferguson. A boy coming out of high school with mechanical dexterity might apply to the Southern for a job, score well on the test, and be sent to the railroad's own vocational school in Knoxville for training as a railroad machinist. The training course took two years and the boy would graduate with an Associate of Machining degree. In those days, this was just as impressive as a five year engineering degree is today. A certified machinist was paid very well and his package included three weeks paid vacation (one at Christmas and two in the Summer), complete health and dental care, and a comprehensive retirement package. |

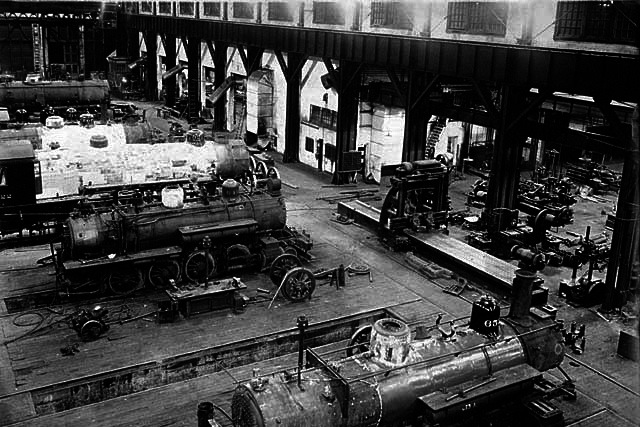

| This is the interior of the engine shop, which is the furthest building on the left in the photo of the whole yard. This is the larger of the two sections of the building. You can see eight full sized engines in for servicing. Engines are stripped down to the boiler, which, because of the high pressure and intense heat, would need to be repaired or replaced every 100,000 miles. This photo was taken on a Sunday afternoon, when the shops were closed. During the week, they would have been bustling with activity. A crew of six worked on each engine: a fully certified mechanical engineer who served as foreman, two welders, two metalworkers, and a pipefitter. The pipefitter's job was to perfect the seals. There were over a hundred seals where various metal parts came together. Any leaking seal meant a return to the shop, which the railroad could not afford. It could take up to a month to recondition a full sized steam engine if it was in bad condition, but they could usually redo one in two or three weeks. |  |

|

The Ferguson Shops were the heart of the Southern Railroad. Every engine on the railroad made visits to Ferguson every 100,000 miles, or more if there were a wreck or derailment or some unusual wear issue. As the most important facility on the whole line, Ferguson was frequently visited by trustees and officials. Visits were usually unannounced so they could get a true picture of how efficiently the shops were functioning. These may have been businessmen with offices in Cincinnati and Atlanta, but they knew railroading from the ground up, and they knew what to look for and what questions to ask of the men they spoke to. Despite their suits and ties, they would poke around the dirt and dust of the shops for a whole day on each visit. |

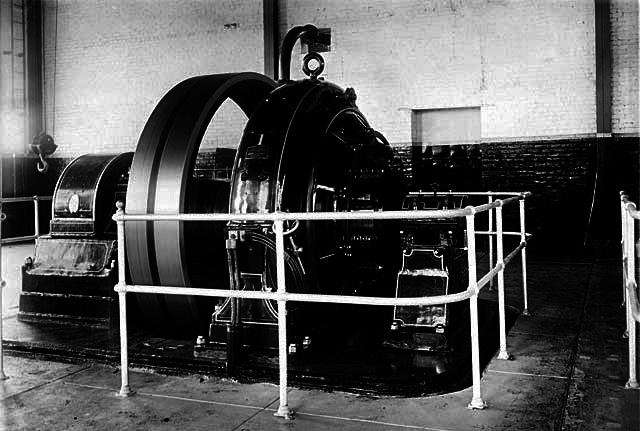

| This is another view of the engine house, showing the wheeling annex. In the yard photo above, this is the smaller section of the engine house, which is the building furthest to the left. While the main crew was working on the boiler and seals, "wheelers" would be replacing the wheels, axles and driving rods. A "wheeler" was a certified railroad machinist who took additional training in how to perfectly round and balance a wheel or axle, and how to balance and fit a driving rod. If a wheel was as much as an ounce out of balance or a sixteenth of an inch out of true, it would set up unnatural wear patterns out on the rails and drastically shorten the life of that engine. Another job a "wheeler" might be asked to do when he had a spare moment was to produce ball bearings. It was a simple job that required incredible precision. A ball bearing had to be perfectly round. Today, 60 years later, with all our modern technology, producing a perfect ball bearing is a challenge. It was a routine job in the Ferguson Shops. |  |

|

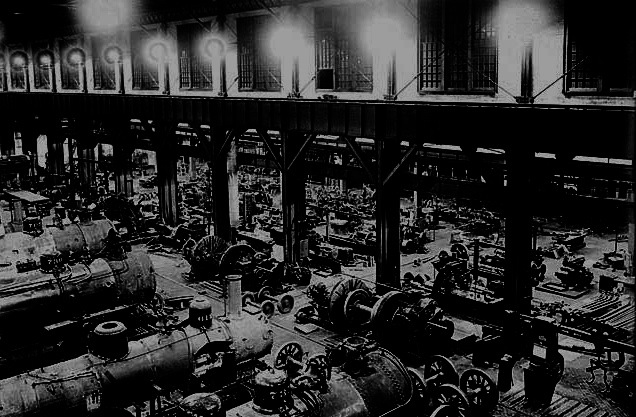

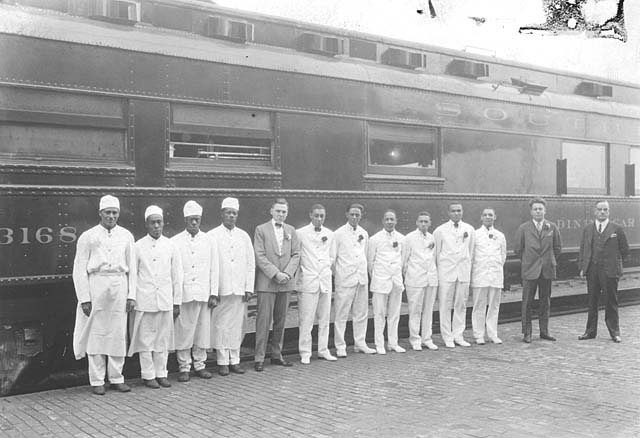

A Southern Railway dining car with full crew and two railroad officials pause in Ferguson on a trip South. Since this was the midpoint of the North South runs, the dining cars needed servicing just as much as the engines did. They would take on additional food, milk, ice and water, have their steam tables repressurized and their rest rooms cleaned. Occasionally a crew member would get on or off here, but that was rare. Usually, the dining crews worked all the way through from one end to the other. |

| This is the interior of the car shown in the previous photo. A railroad dining car was a rolling version of a very high class restaurant. But it had its own ways of operating. The menu was limited to only a few items. You could order a meat, fish or chicken entree and two sides from a list of four or six. You had a choice of three salads and three desserts. The beverage list would include coffee, milk, tea, a white or red wine, apple or tomato juice. However, within this limited menu, the quality would be outstanding. You could not order a better meal in the finest restaurants in Chicago, New York or Atlanta. The meal was included in your ticket. An attendant would come to your seat and offer you a choice of seating times. Breakfast was served from 6 to 9, lunch from 11:30 to 1:30, and dinner from 4:30 to 7:30. Seatings were every half hour. Then the attendant would hand you a menu and take your order. So when you arrived at the car at the chosen time, you were immediately seated and the food was ready. Dishes, bowls, cups and glasses were specially made to hold foods and drinks on the moving trains. |  |

|

This wierd looking car appeared in Ferguson once or twice a month. It was an observation car. Rail road officials would ride the entire line using this car to look for maintenance issues. Notice the staggered side windows. Seats inside were in raised rows, like at a stadium. The men could look out over the heads of the row ahead of them and still see clearly out the front windows, then look out the side windows level with their seats. Note the cowcatcher on the front of the car, designed to move cattle, deer or other animals or if needed any branches or brush that might be laying on the track. |

| This was the Whistle Stop one mile South of Ferguson School. Express passenger trains only stopped at major stations like Lexington, Danville, Ferguson and Knoxville, but Locals stopped at "Whistle Stops" like this all along the line. Pulaski County had Whistle Stops at Science Hill, Eubank, North Somerset, Elihu and Burnside. The engineer would slow, and if he saw passengers waiting, or if anyone on board pulled the cord running along the top of the windows sounding the buzzer, , he would stop. Otherwise, he would keep going. A Local took much longer to cover the same route, but they provided much needed service to rural areas at a time when many families still had no car and many more only had one car. There were no interstates, the best highways were only two lanes, many roads were unpaved, and even good roads were very windy and hilly. Therefore, up until about 1960, it was much faster to travel by train than to drive. People from Burnside, Elihu, Science Hill and Eubank would take the train in to Somerset to work every day. |  |

|

These 2-8-0s stopped at Ferguson for servicing once a month or so. They were off the Southern's subsidiary line, the Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific. These hauled shorter trains, about 50-75 cars, and were designed for basically level terrain. But on the areas for which they were intended they were very fast, so they were suitable for hauling milk, livestock, mail and passengers. Notice the space between the driving wheels and the boiler. This was effective in dissipating heat, which built up due to the high speeds. |

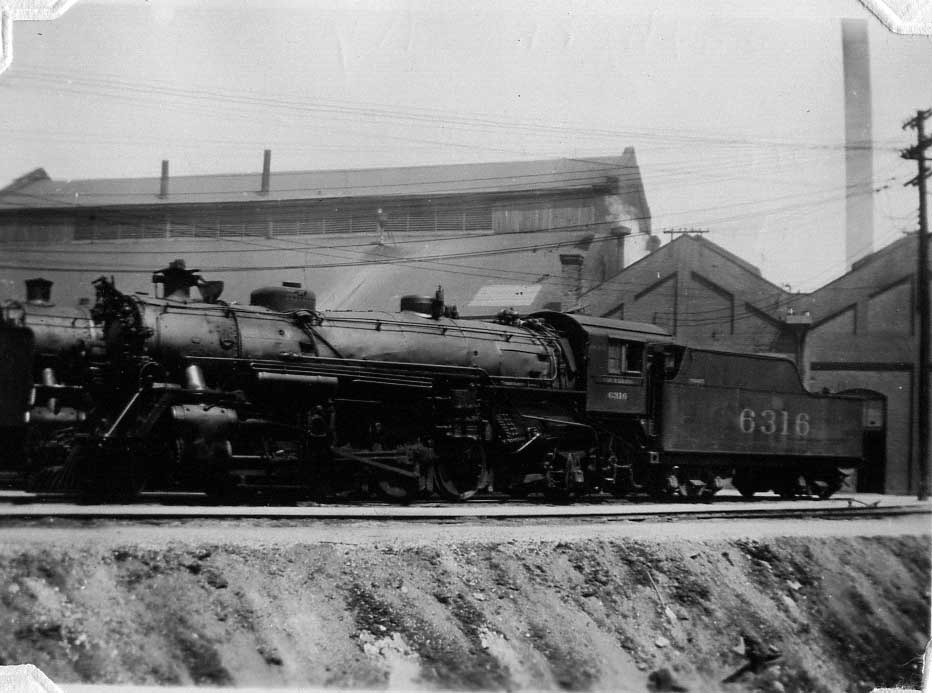

| A 2-8-2 MS-1 Class engine built by Alco Richmond. This was a very powerful engine that could haul long trains up the steep hills of Southern Kentucky and Tennessee. But it needed frequent and heavy servicing. With the Southern running a whole fleet of these engines, it is not surprising the Ferguson Yard was as busy as it was. |  |

|

The steam in the boiler was under pressure. When the engine came into Ferguson Yard for service, the first step was to release the pressure by draining the steam and water. Then the men would refill the boiler with water and refill the tender (the smaller car being towed behind the engine) with wood or coal before sending the engine back on the road. The firepit was at the front of the cab, shown here with someone at the window. The fireman would shovel the coal or wood from the tender into the firepit. The roaring fire would heat the water, converting it to steam, which was used to drive the pistons, which pushed the rods, which turned the wheels. The steam locomotive was a tremendous piece of engineering which hauled freight and passengers across America for 200 years before being sidelined by diesel and electric locomotives. It will probably go down in history as one of the greatest machines ever built. |

This cover of Ties Magazine celebrates the introduction of a whole new kind of locomotive, the diesel electric. This is its maiden voyage on the Southern Railroad. Notice this is a four unit engine. The front unit has the controls and the other three are "helper" units. This is the tunnel and Cumberland River Bridge at Burnside before the lake was backed up. No one realized it at the time, but this was the end of the Ferguson Yard. As they ran the new engines up and down the route, railroad officials soon realized it did not need servicing as often. An engine could go all the way from Cincinnati to Chattanooga, or from Atlanta to Ferguson, between stops. Therefore, a huge savings could be realized by eliminating one of the yards. For two years officials studied the situation before deciding that it would be the Ferguson Yard that would be phased out. The fireman leaning out of the cab is Charles F. Denny of Ferguson. His father, also Charles F. Denny, was Chief Dispatcher on the Southern Railroad's Somerset Section. Soon after this photo was taken, the son enlisted in the Marines and was killed in action after one year of active duty. Ties Magazine was mailed free of charge every month to all employees of the Southern Railroad. |

|

|

Railroading was a mechanical operation. The Southern Railroad needed hundreds of highly skilled mechanics, machinists, welders, electricians, metalworkers and others who could keep the great engines running. Some of these men the railroad imported from elsewhere. Some showed up in Ferguson already trained, applying for jobs. But many graduated from Ferguson, were hired, and sent off to various schools to train for these occupations. By the 1930s, Ferguson had hundreds of skilled craftsmen. |

| It was inevitable some of these men would turn to the automobile for their recreation. They had the tools, training, experience and professional shops at their disposal to work on cars. They could keep a new one running or take an old one and customize or restore it. The yellow 1932 Ford Deuce Coupe above left, the black Chevy next to it, and the 1958 Chevy Impala here right were examples of their pride and hard work. Sadly, as the shops closed, these men moved elsewhere, taking their cars along. |  |

|

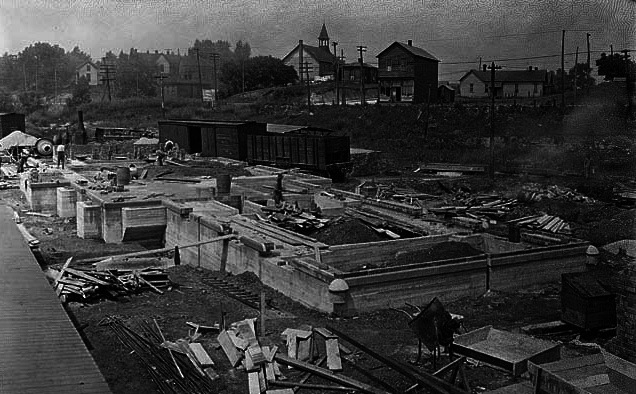

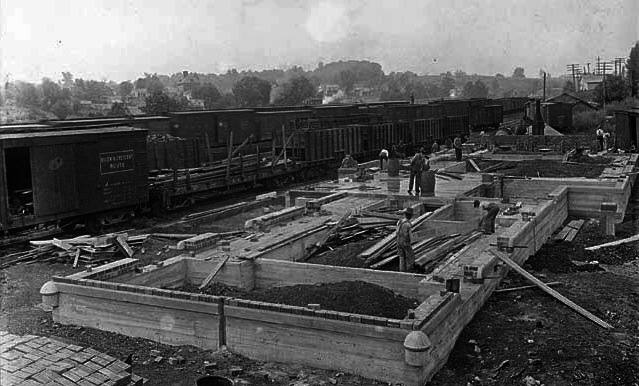

This next series of photos show the construction of the Ferguson Depot, which served both Ferguson and Somerset. Ferguson and Danville Depots had the largest square feet of any Southern station between Lexington and Knoxville. The biggest stations on the Southern were Cincinnati, Chattanooga and Atlanta. |

| The Ferguson Depot was built during the Summer and Fall of 1916. The lumber in it was timbered in Pulaski County on bluffs overlooking Rockcastle River. The bricks used were mixed and fired in Pulaski County near Burnside. The heavier stones came from quarries down in Tennessee, the slate shingles came from quarries near Calhoun,Georgia and the glass in the windows came from the Cincinnati Glass House. Foremen were brought in by the Southern Railroad but the workers were hired locally. |  |

|

Railroad stations and trackside buildings had to be built much stronger than other structures because the trains passing so close several times a day set up vibrations in the ground or the rock layers which could be destabilizing. Close attention was paid to foundations, corners, wall tie ins and roof beams. Joints had to be fitted with less tolerance and bolts, dovetails and mortises had to be tight but with a little spacing so the vibrations could pass through the building without damaging it. |

| In this photo the shell of the station is complete but the interior needed a month's work. Bathrooms received special attention. Railroad officials often said passengers judged a railroad by its bathrooms as much as anything. A spacious, clean and plush bathroom made an outstanding first impression and sent the passenger out to the train already in a good mood. Officials also made sure their waiting rooms were very large, with high ceilings, comfortable benches and plenty of big windows and bright lighting. The Ferguson Depot also contained ticket windows, coffee shop (the closest thing to a snack bar they had in 1916), gift shop and luggage claim area. |  |

|

This is the finished station. Ferguson was a very upscale stop. The Southern Railroad's finest trains stopped here twice a day in each direction. People from not only Pulaski County but counties west all the way to Campbellsville and Glasgow and south to the Tennessee line had to come here to catch the trains because they didn't stop at the smaller towns. The Royal Palm, for instance, passed through Pine Knot, Stanford and Burnside but did not stop. By the 1950s the Royal Palm was considered the elite train because it went all the way to Florida. But for most of the 50 years the Chattanooga Choo Choo was the most prestigious. It had been the first passenger train to connect North and South as it ran between Cincinnati and Five Points, which became Marthasville, which became Atlanta, a decade before the Civil War. The Chattanooga Choo Choo had a song written about it and a movie made about it. It was a high speed express luxury train which stopped only in Atlanta, Chat- tanooga, Knoxville, Ferguson, Danville, Lexington and Cincinnati. Movie stars, executives and politicians briefly stretched their legs here. |

|

This vehicle was a familiar site to anyone growing up in Ferguson in the late fifties or early sixties. It is a Southern Bell Dairy delivery truck. This truck delivered fresh milk every morning to the Ferguson cafeteria. It also stopped by two stores in Ferguson, then made its way south out of town to Burnside, where it stopped at the school and several more stores. |

| A wheeler (under the exhaust pipe) comes on duty while a coworker kneels over a pile of sheeting in the lower right corner. These machines, carefully railed off to prevent accidents, were used to grind, smooth, and "true" wheels for the big engines or occasionally a freight or passenger car or caboose. The wheels were too big and heavy for the men to move by hand. They were moved into place and picked up off the machines by specially adapted fork lifts. Although long gone from Ferguson, the same machines are still being used at rail shops in other states. The modern versions use computers, lasers and digital readouts to fine tune curvatures, but the basic principles remain the same. |  |

|

This is another view of the same scene as above (the exhaust pipe on the right is the same one seen in the previous photo). These jobs were extremely high paying but were very difficult and dangerous. After a decade of this work, a man was almost guaranteed to be at least partially deaf because as the grinders smoothed out the large heavy wheels they made a terrific screeching noise, and no one back then wore ear plugs. Frank Muse dismissed the skill involved. "Just think of a lathe with a long piece of wood you're making into a chair leg. Here the lathe is very short, the long cylinder is a narrow disc, and instead of wood we use iron. But the concept is the same." |

| This is the Heavy Fabrication Wing. Here a good machinist could make any part needed. The big machine to the right is a state of the art drill press. Notice all the small wheels and "X" cranks. They were used by the operator to adjust various angles. The machine behind it was a Flanger, used to form curved parts. A machinist could operate any one of these machines, but he would specialize in one. In some locations men might move from one machine to another, but Ferguson had a large workforce so one man would rarely leave his specialty. He could be a Drill Press Operator for 30 years. These were very expensive machines and when the Southern Railroad closed the Ferguson Shops they loaded all of them very carefully onto flatcars and hauled them down to Chattanooga. Some of them are still in use. You can see them at the Chattanooga Rail Center. |  |

|

This was the control panel for the high pressure hydraulic hoses which powered the machines. It's interesting to realize that 100 years ago, using nothing but air, water and steam pressure, men could work on huge engines weighing many tons. We like to think that our modern technology is far superior in the 21st Century, with computers, robots and electronics. |

|

|

This is a rear view of one of the wheeling complexes. |

|

|

The workbench. Each man had his own area and would keep his own tools in the drawers and lower shelves. They could work here on fine detailing a part or an assembly of several parts, like a valve or housing. This would also be where they would disassemble a unit to get down to the part that needed reworked or replaced. Notice the big windows plus the intense overhead light banks. A man had to have good eyes, and needed plenty of light to see tiny details down to a sixteenth or 32nd of an inch. They talked of "variances," which meant the difference between the set measurement for a part and the measurement of the part they made. Usually a 64th of an inch variance was the maximum allowable. |

| Another view of the Engine House with Wheeling Annex in the background. Notice in the engine in the foreground the new boiler section that has just been installed. The long narrow slot in the floor allowed men to get down under an engine to work on the bottom. |  |

|

This is looking from a rear corner of the Wheeling Annex out toward the Engine House. All of these photos were taken on a Sunday afternoon when no one was working. During a normal day, over a hundred men were in this building and it would have been crowded, noisy, and very busy. |

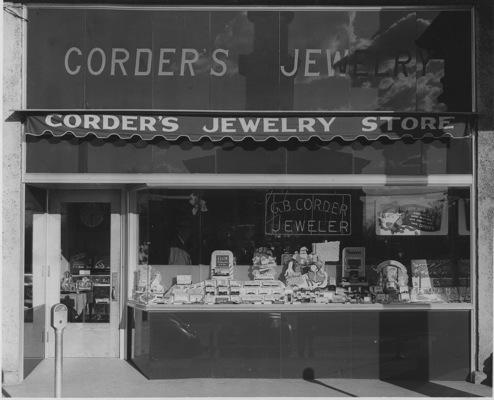

| Only the older Ferguson graduates will remember Corder's Jewelry Store. It was very popular and sold very high class merchandise, but closed in 1958. For a girl to receive a Christmas or birthday gift from Corder's was very special. Many 1950s Ferguson girls received their engagement rings from Corder's. |  |

|

As the car culture took over after World War II, Pulaski County, like everywhere else, saw the rise of the drive in restaurant. A favorite thing to do was stop by the local drive in on the way to or from a game or a movie, or just as a destination in itself. Somerset in the 1950s saw half a dozen drive ins opened. The most famous of these, Finley's, lasted three decades through several remodellings, and its Finleyburger is still fondly remembered by Ferguson graduates. The owner, Lester Finley, is still alive and in business over in Corbin, where he owns Sweet Hollow Resort. Finley's was also famous for its French Fries, Onion Rings, and Milkshakes. |

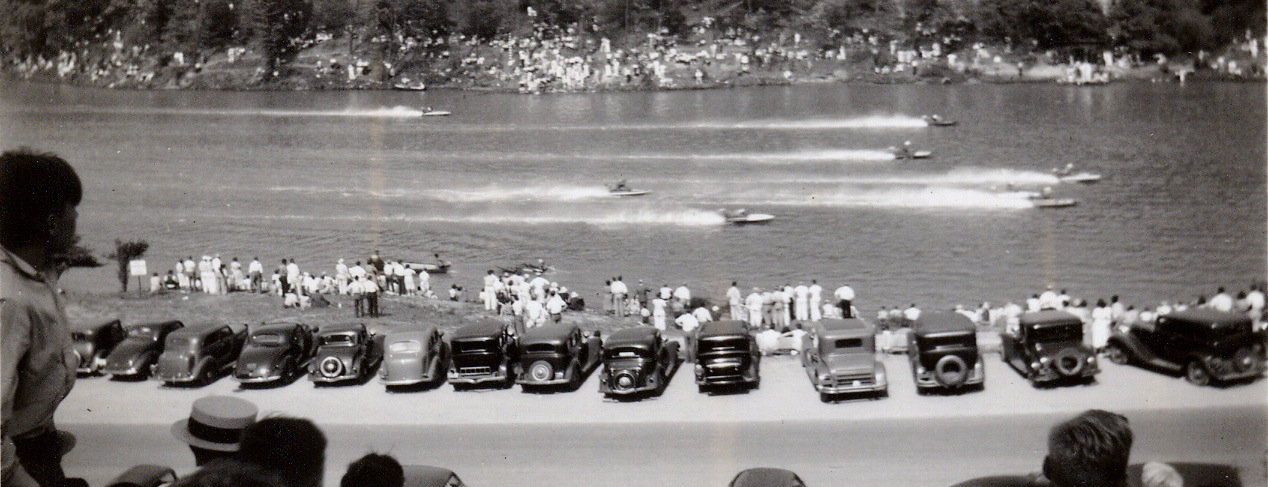

| Before the dam was built and Lake Cumberland was backed up, they used to hold annual speedboat races down on the Cumberland River every August. Fans would come from as far away as Lexington and Bowling Green for the weekend. This photo was taken in August of 1938, below where the Big South Fork emptied into the main river. |  |

|

The Ferguson Firewagon of 1918. The Southern Railroad housed this contraption at the Ferguson Rail Yard, but it could be used anywhere in town. At first they hitched horses to it, but eventually they towed it with a truck. One man operated a pump, which built up pressure to force the water through the hoses. Fire was always a danger along the railroad tracks, because hot ashes and sometimes burning coals would shoot out of the engine smokestacks and land on tarpaper roofs of nearby houses or in dry leaves on the ground. This firewagon saw plenty of action. |

| Even though Ferguson was primarily a railroad town and most of its men worked for the railroad or in timber, many people on the edges of town still farmed. They had to get their corn milled, and this was one of the mills they went to. It was along Pittman Creek. Notice the mill wheel in the lower right. A dam across the creek forced the water into a side channel where it turned the wheel, and thus the grinding wheel inside. Housewives would come here to buy their corn meal and flour. The land around Ferguson was too hilly to raise wheat, but further out in the county, around Nancy and Eubank, they did raise it. There were no streams in those areas with enough flow to turn the big wheels, so they would have to bring their wheat here or to similar mills at Burnside or Shopville. This is a 1930 photo. |  |

|

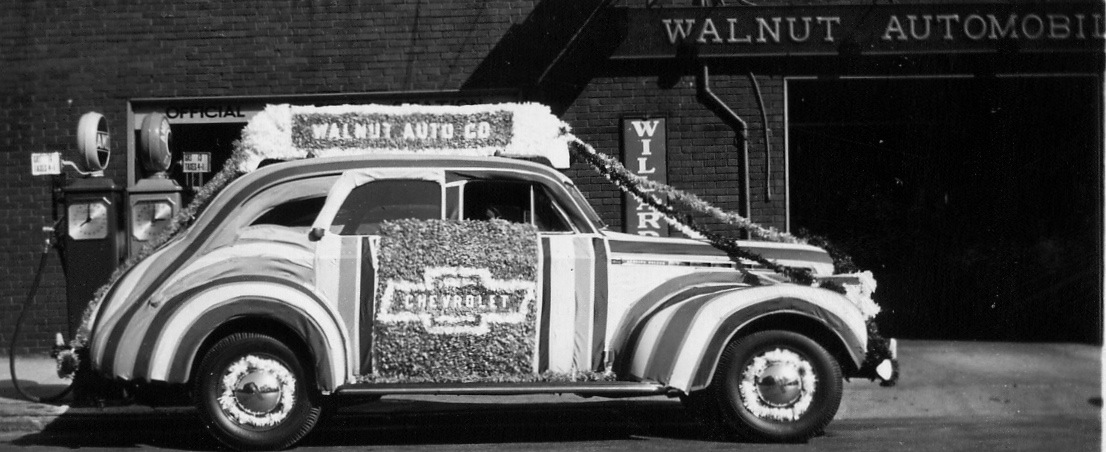

This July 1940 picture shows the Walnut Automobile Dealership in downtown Somerset. They sold Chevrolets. This car is decorated for the annual Fourth of July Parade. Notice the old gas pumps just behind the car. |

| This was the Meece family houseboat, one of the first ones on the river during the first Summer after they closed the gates on the new dam and backed up Lake Cumberland over the town of Burnside. |  |

|

Many of the old timers say the deepest snow Ferguson and Pulaski County ever saw was during January of 1964. Kids and dogs loved it. The adults, who had to shovel it and drive in it, were less thrilled. |

|

For boys growing up in Ferguson Pit- man Creek was a special place. Many of them learned to swim, fish, paddle a canoe, and camp out "down Pitman." Many of them also smoked their first cigarette and drank their first alcoholic beverage "down Pitman." The creek comes all the way from north Pulaski County, but Ferguson boys mostly explored it from Route 80 to Burnside. |  |